The Tokyo Anime Award Festival held a symposium on March 10 to discuss the impact that digitization will have on the Japanese anime industry. The discussion was held between veteran animator Toshiyuki Inoue (Maquia – When the Promised Flower Blooms, Ghost in the Shell key animation), Kiyotaka Oshiyama (Flip Flappers director, DEVILMAN crybaby devil animation director), and Ryo-timo (Yozakura Quartet ~Hana no Uta~ director, Birdy the Mighty: Decode chief animation director).

Toshiyuki Inoue has worked in the animation industry for over 35 years and acts as a mentor to young animators. Kiyotaka Oshiyama regularly works with digital animation and has recently been working on a digital anime production almost entirely by himself. Ryo-timo is one of the pioneering digital animators in Japan, and his work on Birdy the Mighty: Decode sparked a “webgen” animation movement.

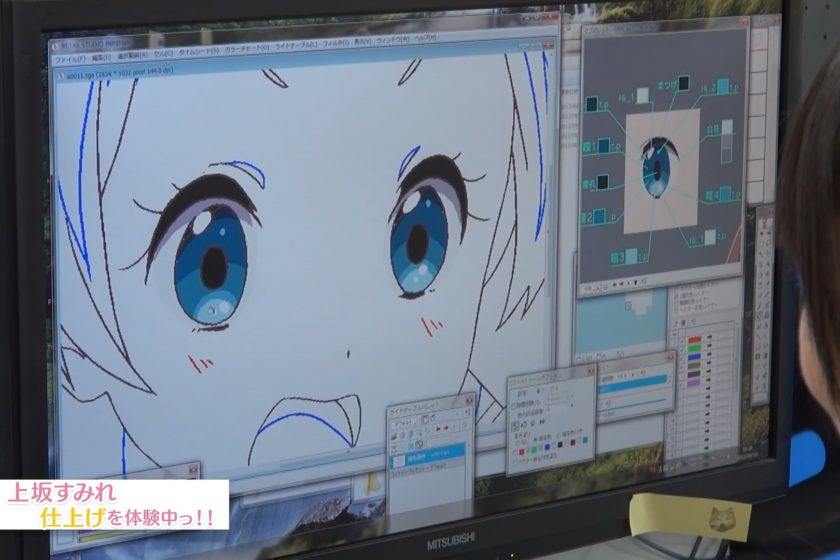

“Digital animation” refers to the use of tablets and computers to aid the animation process. The three animators explained that in the Japanese anime industry, the compositing and coloring processes are now completely digital. Although it is not the industry standard yet, it is now becoming more common for storyboards and key animation to be drawn on tablets. This streamlines the production process, and allows the finished look to be achieved more quickly.

Inoue spoke positively about this change, but voiced his concern that digital animators could be exploited because of pay rates and role specifications that were decided many years ago. It is standard in the anime industry for key animators to be paid per cut or drawing, but by digitizing the process, they take on some of the work that would be ordinarily be handled by the compositing or finishing teams. “I want the industry to hurry up and formally recognize that the compositing work a digital animator does independently is worth extra money, too,” he said. “The way things are in Japan right now, it doesn’t look like animators are getting paid more for their work.”

Ryo-timo suggested that digital animation shouldn’t be paid per drawing or cut, but by the hour instead. All three speakers recognized that the animation industry needs to change when it comes to animator pay rates.

On the other hand, Oshiyama pointed out that digital tools can allow for smaller teams to put out high quality work. This could alleviate the quality issues caused by throwing a large number of animators at a project in order to get work done quickly. Instead, productions could just hand-pick a small number of animators who are skilled in digital animation. This could improve productivity and reduce costs at the same time. “However, you mustn’t get the incorrect impression that just because there are a small number of people working on it, it’s okay to pay them less,” Oshiyama stressed.

The symposium closed with a discussion about current problems facing the anime industry. There are too many anime productions and not enough skilled animators to work on them. Anime character designs are also too complex these days, which means that it is not possible to draw animation frames quickly, especially compared to the past. The low pay rates for animators today originated from an earlier time when animation was done quicker.

“Now that the animation process is changing, now is as good a time as any to re-evaluate payments,” the speakers agreed.